ESMO 2014 Cancer Congress bans Press, Nurses and Patient Advocates from Exhibits and Symposia #ESMO14

George Mason was a delegate from Virginia to the U.S. Constitutional Convention and was instrumental in drafting the Bill of Rights, what we now know as the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution. His opinion was that:

“The freedom of the press is one of the greatest bulwarks of liberty, and can never be restrained but by despotic governments.”

In 1789, the Bill of Rights and the First Amendment to the Constitution that guarantees freedom of the press in the United States came into effect.

Freedom of the press is one of the hallmarks of a civilized society. The ability to publicly debate ideas and information underpins Western notions of democracy.

So, with this fundamental principle in mind, I believe we should take seriously the restrictions on the press at the forthcoming Congress of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) in Madrid.

At the 2013 European Cancer Congress in Amsterdam media were banned from entering the exhibit hall along with patient advocates and anyone not considered to be a healthcare professional (HCP).

It was bizarre to see company staff unable to access their own exhibit booth if they didn’t have a badge that designated them as an exhibitor or HCP.

ESMO have taken this further in Madrid by banning media, nurses and patient advocates from satellite symposia as well. These industry sponsored symposia start at the conference venue immediately after the opening ceremony, and run all day Friday and then every evening.

Even if ESMO has no responsibility for their content, they are clearly sufficiently part of the Congress programme if ESMO can decide who shall and shall not be permitted to attend them!

Patient Advocate Protest at 2013 European Cancer Congress

Patient advocates in Amsterdam for the 2013 European Cancer Congress staged a demonstration in protest at being barred from the exhibit area as reported by eCancer News:

Patient Advocates protest exhibit hall ban at 2013 European Cancer Congress. Photo credit: eCancerNews/Jan Geissler

Jan Geissler (@JanGeissler) patient advocate and co-founder of CML Advocate Networks in Switzerland succinctly wrote at the time:

Patient advocates attend in their capacity as experts, with most of them being members of government committees, regulatory authorities, research groups and healthcare advisory boards. Information shown in the exhibition is available without access restrictions on the internet, on authorities’ websites, and in medical journals. Patient advocates must be entitled to access all information as equal stakeholders in healthcare.”

I agree with the sentiments expressed by Jan, and they equally apply to journalists when it comes to access to information.

The media plays an important role in engaging the public on health topics, holding companies to account and critically analyzing and sharing data about new drugs and treatments. We should not be denied entry to industry symposia at major medical meetings where novel targets and new drugs in development are being discussed by world class experts.

I am disappointed that what took place in Amsterdam last year with security guards barring access was not a one-off, but will be continued – and even extended – at ESMO 2014 in Madrid.

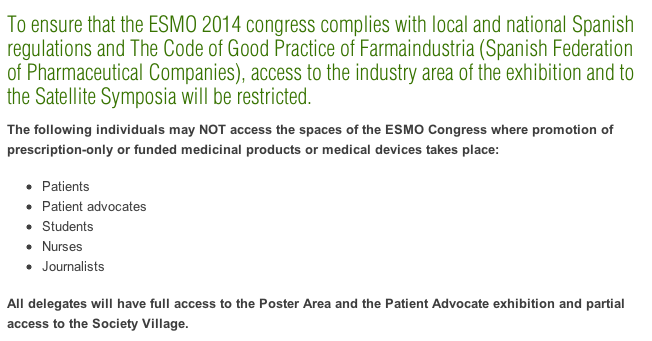

ESMO 2014 Access Restrictions

ESMO have advised on the Congress web site that journalists, patient advocates and nurses will be banned from access exhibit hall and industry satellite symposia at the forthcoming meeting in Madrid.

While I appreciate that many of the assembled media never venture outside of the press room at conferences, I think that we should be concerned about restrictions on access to information at medical meetings.

Cancer conferences in Europe should be inclusive not exclusive. The trend towards created two-tier access to information, which started in Amsterdam and now continues in Madrid, is not a positive development.

Cancer treatment is multi-disciplinary and inclusive with patients, nurses and doctors all sharing in treatment decisions.

From this perspective, banning nurses and patient advocates from the exhibit area and access to information such as picking up a brochure about new treatments or clinical trials is not how the treatment of cancer is done in the 21st century.

Not only is much of this information already readily available on the internet, but ESMO are restricting access to satellite symposia this year, many of which are educational in nature, or discuss drugs in development that are not publicly available on the market. As such, it’s hard to believe why rules and regulations on advertising should apply in this case.

You can’t advertise something you can’t yet sell, or be accused of promoting a drug that’s not available to prescribe.

Regulatory Background

ESMO state that the access restrictions are necessary in order to comply with “local and national Spanish regulations and The Code of Good Practice of Farma industria (Spanish Federation of Pharmaceutical Companies)” and provide the following quote in support of their position:

“It is expressly prohibited to advertise: (a) prescription-only medicinal products, (b) medicinal products funded by the Spanish Health National System; and (c) psychotropic substances, to individuals other than to healthcare professionals qualified to prescribe – or supply – medicinal products.”

ESMO cite the Code of Practice of the Spanish Federation of Pharmaceutical Companies, but is this legally binding on them as a Congress organizer? I am not qualified to interpret Spanish law, but a code of practice is typically administered by a trade association and applies only to its members, in this case pharmaceutical companies, and has no independent legal effect. If ESMO is acting to protect the interests of pharmaceutical companies, they should say so.

Given ESMO have had over a year to understand the legal issues raised at ECCO 2013, to just put up a web page with references to laws but with no explanation as to why ESMO interpret them the way they do should not be deemed satisfactory for an organization of oncologists that base treatment decisions on scientific evidence.

Where is the legal analysis that supports ESMO’s need to take the extreme conservative position it has? I would have expected more analysis and explanation to be offered.

Although not cited by ESMO, from my limited research I believe the underlying problem is European Directive 2001/83/EC, “Community code relating to medical products for human use.” This Directive establishes a code that governs the placing on the market, production, labelling, classification, distribution and advertising of medicinal products for human use within the European Union (EU). Title VIII of this Directive regulates advertising.

In essence, it states that only those who can prescribe medical products should be exposed to advertising and advertising should not be made to the general public (everyone who doesn’t have the power to prescribe). The intent is to protect the public and require that they obtain information on prescription drugs from their doctor.

Readers may recall that EU Directives create rules and regulations that all member countries have to abide by. However, they are not self-executing, a directive only comes into effect through national law in each country, which is why several of the Spanish decrees that ESMO cite no doubt codify the requirements of the Directive.

The argument that results is that since anyone in theory can buy a ticket to attend ESMO, it’s a meeting that’s open to the “general public”, hence the need to restrict access to parts of the meeting where there is medical advertising.

However, if ESMO are seeking to be compliant with European medical advertising law, then it should not matter if you are journalist, nurse or patient advocate, the question is simply are you a healthcare professional who can write a prescription?

Segmenting attendees in the way ESMO is doing to restrict access ignores the fact that not every person with a medical degree has the right to prescribe. Some journalists may in fact be medically qualified prescribers. Equally, all nurses should not automatically be excluded, some now have the right to prescribe too.

In England, there are now nurse independent subscribers, pharmacist independent subscribers and optometrist subscribers. See: Who can Write a Prescription? In the United States, many nurse practitioners have replaced primary care doctors and perform the same roles as a family doctor or GP. ESMO’s sweeping exclusion of ALL nurses therefore makes no sense in this context.

What makes the ESMO categorization of who has restricted access at the meeting even more surprising is that no mention is made as to whether researchers who are scientifically qualified will be excluded? If you are scientifically qualified with a BSc, MSc or PhD and lack prescribing authority can you enter the exhibit area or satellite symposia?

Indeed if ESMO want to be consistent in their compliance with European Law, they should restrict the access of their members who are not medically qualified. Whether ESMO choose to do this remains to be seen.

If they do apply the rules consistently then one person affected would be Peter Boyle, who will receive a 2014 lifetime achievement award in Madrid.

He was the first non-medical oncologist to be elected to membership of ESMO, and is a Professor of Global Public Health at the University of Strathclyde, but is a statistician by training.

According to the Spanish Pharma Industry Code of Practice that ESMO cites, he should therefore excluded from the satellite symposia and exhibit hall since he has no right to prescribe a medicinal product and be exposed to advertising.

Professor Boyle should be entitled to attend all parts of the ESMO meeting, and I mention him only as an example that highlights the absurdity of enforcing this type of advertising regulation at medical meetings such as the European Cancer Congress in Amsterdam or ESMO 2014 in Madrid.

Should European Regulations apply to US based Journalists?

ESMO’s ban makes no distinction as to where an attendee comes from. I would argue that European Law should only apply to Europeans, in the same way that international physicians at US medical congresses have access to information that can’t be shown under FDA rules to US doctors. Pharma companies handle this without problem via special booth sections (“booth within a booth”) that only international attendees can gain access to.

In the same vein, if one looks at Google’s “right to forget” it only applies to those subject to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice ruling i.e only Europeans have a right to the benefits that European laws conveys.

European regulations are intended to protect the European public, if you are not from Europe should the restrictions apply to you?

It’s hard to see a Spanish Regulatory Agency seek to enforce rules and regulations designed to protect the general public in Spain against a United States based journalist. This was a view taken by a representative of the Dutch regulatory agency I spoke to last year.

While I am not in favor of any restrictions on access to information, I’d argue that the Spanish Code of Pharma practice cited by ESMO is intended to govern how pharma companies interact with doctors in Spain, not conference attendees from the United States, Middle East, Africa, Asia or Australia. They should certainly not be applied to American journalists not governed by EU Directives.

As an example of how other medical societies are approaching this issue, last year at the annual meeting of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) in Amsterdam, the largest medical meeting in Europe with 30,000 attendees from 150 countries, I was told by a journalist who attended that the only people prohibited from the exhibit hall were non-healthcare professionals from the Netherlands. Attendees from other countries were not excluded, including journalists!

The European Society of Cardiology Press Office did not respond to two requests for comment on how they ran a successful meeting in compliance with Dutch advertising regulations, and the implications of such rules for European medical societies.

That said, the measured approach that ESC is anecdotally reported to have adopted in Amsterdam makes intuitive sense.

Spanish rules and regulations exist to protect the Spanish, and not the citizens of the United States or other countries who may attend. If ESMO were to adopt the approach taken by the European Society of Cardiology last year in Amsterdam, the only people with access restrictions in Madrid would be Spanish non-healthcare professionals.

Similarly in the US, the States of Minnesota and Vermont have rules governing physician access to hospitality to avoid any incentive to prescribe, so pharma companies carefully screen attendees at their booths based on their badges when doling out cupcakes and ice cream.

Such restrictions to Spaniards would no doubt affect far fewer people than the highly conservative approach ESMO have chosen to adopt with a blanket ban on journalists, nurses and patient advocates irrespective of their country of origin.

I am disappointed that in the year since this issue came to the front at the 2013 European Cancer Congress in Amsterdam, ESMO’s response is to lamely hide behind rules and regulations, which fundamentally make little sense when applied to international attendees at a global medical meeting.

Even if ESMO lawyers don’t accept the argument that Spanish healthcare rules should only apply to the Spanish, there are several things the organization could have done over the past year to mitigate European Advertising Regulations and avoid the need for the blanket type of discrimination that will take place in Madrid.

My management approach is one where I expect people not to tell me problems, but bring me solutions – here’s a few suggestions I would like to offer ESMO:

How ESMO could have done things differently

1. Satellite Symposia could be educational not promotional

Satellite symposia could be educational and not “sponsored” promotional events. That’s the case at US meetings, where professional medical education companies organize the events with independent grant support from pharma companies. Such events are not promotional and usually provide fair balance.

While I can appreciate why pharma companies might not like this idea, there is no reason why ESMO couldn’t adopt such a policy, and in the process avoid having to restrict access to them.

Those satellite symposia at ESMO 2014 that are being conducted on the US model could easily be classified as educational without any restrictions on access.

2. You can’t advertise a drug you can’t prescribe

Companies can only advertise drugs that have a marketing authorization, so when you talk about drugs in development you are not advertising anything. After all, the drug in development may never make it to market and be available!

Those satellite symposia that focus on drugs in development and novel targets should not therefore be considered advertising or promotional events.

AstraZeneca’s immuno-oncology symposia will no doubt discuss AZD9291 and their anti PD-1 inhibitor, MEDI4736, both drugs in development, where information presented about them can’t be advertising since they are not approved and you can’t prescribe them.

It’s a great disservice to those attending the meeting for world class experts to be invited to present at such a symposia and to then restrict access to events with significant scientific merit.

At ESMO 2012 in Vienna, for example, we wrote on Pharma Strategy Blog about an educationally orientated satellite symposia on pancreatic cancer, which only focused on science and drugs in development.

A similar opportunity is now denied at ESMO 2014 through the ban on media attending such events. There should be no restriction placed on what material a pharma company can share with journalists.

Would the FDA restrict what information is given to a journalist at a US medical meeting, irrespective of where they came from? The answer is No. America has many failings, but in this respect it is way ahead of Europe.

Satellite symposia that focus exclusively on drugs in development, science and new targets should not have any restrictions on access placed on them because advertising regulations don’t apply if it’s not about marketed drugs.

Update Sep 13:

EU patient advocate @jangeissler advised me by Twitter that the European Medical Advertising Directive 2001/83/EC states that it does not apply to “Medicinal products intended for research and development trials” i.e. drugs in development. See Title 1, Article 1. Given Spanish law has to follow the Directive, there appears to be no reason why there should be any restriction placed on access to satellite symposia that only discuss drugs in development. Even ECCO 2013 in Amsterdam did not ban anyone from the industry satellite symposia, and the EU rules/regulations were the same in Holland!!

3. Create a Booth within a Booth

At medical meetings in the United States such as the ASCO annual meeting, many companies have a ‘booth within a booth’ where only international attendees can receive information that US physicians are not entitled to see. Entry to this separate area is controlled and only delegates with a non-US badge are admitted.

ESMO could have required that companies create a ‘booth within a booth’ concept that addresses European advertising regulations. An internal area with adverts could be for prescribers only, while the outer area could have general information about drugs in development, clinical trials, the mechanism of action and science of pathways, pipeline etc and company branding.

When I spoke last year in Amsterdam to ECCO CEO Michel Ballieu, he told me this was a valid option that would avoid having to discriminate who got access to the exhibit hall. ECCO did not consider implementing this due to lack of time as they only became aware of the regulatory issues in Holland a few months prior to the start of the Congress.

While it would undoubtedly cost pharma companies money to make changes to their booths, it would not have been an unreasonable request by ESMO, especially as the same companies do this in the US already.

Implementing such a policy would rightly put the obligation on enforcing who is exposed to advertising on pharma companies. Company staff on an exhibit could then inquire whether a nurse or pharmacist had prescriber authority before giving them access to the prescriber area.

However, the easiest solution that ESMO could have implemented is the one that appears to have been adopted by the European Society of Cardiology who are hosting the largest medical Congress in Europe from August 30 to Sep 3, 2014 in Barcelona.

One would expect that they would have needed to adopt the same draconian restrictions that ESMO has in order to comply with Spanish law, however an examination of the ESC 2014 website and programme material suggests there are no restrictions in place at their meeting.

The ESC 2014 website says that delegates gain access to

- Access to all scientific sessions.

- Access to Industry Sponsored Sessions.

- Access to the exhibition of approx. 30 000 square metres. The exhibition will be open on Saturday, Sunday, Monday and Tuesday.

- Access to the Emerging Technologies Showcase Area (ETSA), an exclusive area dedicated to innovative biotechnology, devices, software, equipment, products or services.

Why is that? Cardiologists are subject to the same European Directive Medical Oncologists and same Code of Practice for the Spanish Pharmaceutical Industry applies to both meetings.

My hypothesis is that ESC may have found a simple and elegant answer:

4. Make the meeting one that is not considered to be open to the general public

The role of lawyers is to both mitigate risk and interpret the law in an effort to find creative ways around rules/regulations, particularly ones that make little sense in how they are applied. Legal rules and regulations are rarely black and white but exist in shades of grey, open to interpretation by judges and lawyers.

I’m not a regulatory professional or European lawyer, but the key issue from my reading of European Directive 2001/83/EC is its repeated use of the word “general public,” and the intent of the directive to avoid exposing the public to advertising of medical products that they are not qualified to evaluate.

If anyone can register for a medical meeting such as ESMO, then there’s a conservative legal argument to be made that restrictions on medical advertising that apply to “general public” are appropriate.

But what happens if your meeting is in effect a private one, and not open to the general public?

I would argue if a meeting is not open to the general public i.e. it’s a private meeting, then rules and regulations on medical advertising designed to protect the general public should not apply. After all there’s no risk of harm if there’s no public who might be harmed.

This appears to be the approach adopted by the 2014 Congress of the European Society of Cardiology in Barcelona, which puts conditions on ESC 2014 registration that in essence make it not open to the “general public.”

In reality, a cancer meeting such as ESMO is where professionals come together to inform themselves about cancer care. It’s not a meeting targeted at the general public.

Like the 2014 European Cardiology Congress, the stakeholders at ESMO include industry representatives, certified healthcare professionals, accredited media and researchers, patient advocates i.e. those who are involved in the science, management and prevention of cancer.

If ESMO were to require all delegates to fall within a designated professional category as ESC appear to have done i.e. one of the above stakeholder buckets, is that a way round the advertising restrictions? I’d be interested in a legal opinion on whether this a valid argument or not.

The only losers from this approach might be any patients who might want to attend in an individual capacity, but all those I know that attend medical or scientific meetings have been representatives of patient advocacy groups, and attending in a professional rather than personal capacity. The steep registration fee is usually a barrier to entry to deter members of the general public from attending.

Have ESC cracked it? I don’t know, but what is surprising is the apparent difference in approach adopted by ESC and ESMO for a major Congress in the same country within a month, where they both face the same regulatory challenges and are governed by the same Spanish Code of Practice. No doubt many of the same pharmaceutical companies will be at both meetings.

Do European medical societies talk to each other? I certainly would have expected a consistent approach to what is in essence a shared problem across all medical disciplines.

Medical congresses have big clout in terms of the revenue they bring to local economies, and I’d expect them to work out pragmatic solutions with country regulatory agencies that avoids the need for course of action that ECCO took in Amsterdam and ESMO plan to to do in Madrid.

If anyone attends ESC 2014 I’d grateful for an update as to whether there are any restrictions on delegate access to the exhibit hall or any industry symposia since the above is only my theory and I could be totally wrong as to what happens in practice in Barcelona.

My Conclusions:

I hope that in writing this piece it will stimulate further debate on the role of the media in communicating medical information in Europe and how advertising rules, which ostensibly were never intended to be applied in the way they are, can be effectively overcome or their effects mitigated.

European medical societies and pharmaceutical companies could use their lobby influence for an exemption on advertising rules at medical meetings, one that allows journalists and patient advocates to receive and share information on prescription drugs.

When societies host conferences in countries with zealous regulators, they could pursue strategies that are less divisive and more inclusive, such as creating a ‘booth within a booth’ in the exhibit hall.

Medical societies across disciplines should talk to each other and adopt a common position. What ESC does in Barcelona should be no different from what ESMO does in Madrid. By grouping together and adopting a common position medical societies can wield an economic sword by taking their business to countries whose regulatory agencies are willing to work on solutions rather than create problems.

Restricting the freedom of the press and creating a two-tier access to information at major medical meetings is both pernicious and toxic.

Sadly, ESMO appears to have learnt little from what took place in the Netherlands and the documented protest by European Patient Advocates at the 2013 European Cancer Congress. If anything, the restrictions at the Madrid meeting are even more draconian and exclusionary than those that were in place at Amsterdam.

I am dismayed that ESMO chooses to hide behind anachronistic rules and regulations. This is not the way forward, particularly when the solution may be as simple as the approach that the European Society of Cardiology appear to have adopted for their 2014 Congress in Barcelona by making the Congress in essence not open to the general public.

This article only reflects my personal opinion. I welcome comments from any stakeholders or interested parties that wish to offer alternative perspectives, additional insights or commentary to what is a topic that impacts all with an interest in European cancer care and the dissemination of information.

Update Sep 1, 2014: ESC Congress in Barcelona has no press restrictions

Thanks to the power of Twitter and Jacob Plieth (@JacobEPVantage) who followed up with colleague Elizabeth Cairns (@LizEPVantage who is attending the European Society of Cardiology Congress in Barcelona, it has been confirmed that there are no restrictions on the press entering the exhibit area or any satellite symposia.

@JacobEPVantage Exhibit hall certainly. Haven’t had a chance to try a satellite. — Elizabeth Cairns (@LizEPVantage) September 1, 2014

@JacobEPVantage #ESCcongress staff member confirms that press are allowed into satellite symposia — Elizabeth Cairns (@LizEPVantage) September 1, 2014

Now this has been confirmed as predicted, it begs the question of why the forthcoming European Society for Medical Oncology Congress in Madrid is any different?

After all, it’s taking place in the same country where the same regulations and royal decrees apply. There should not be in any difference in how a European cardiology congress is run as compared to an oncology one. So far, the response from ESMO via Twitter (@myESMO) has been a bit underwhelming, with a rather lame “we need to work within local framework.”

@3NT @MaverickNY Fully understand your concerns. Complex situation for ESMO as we need to work within local framework… #ESMO14 — ESMO – Eur. Oncology (@myESMO) August 25, 2014

How is the “local framework” in Spain any different for other medical societies than for the European Society of Cardiology? I find it hard to believe Europe’s largest medical congress is not equally risk averse when it comes to ensuring compliance with Spanish rules and regulations.

I do think that an explanation of why ESMO have adopted such an extreme and draconian position as compared to ESC is in order, don’t you?

@myESMO any comment on why press can go into exhibits and satellite symposia at #ESCCongress but not at #ESMO14? Same country & rules! — Pieter Droppert (@3NT) September 1, 2014

Update Sep 15, 2014 ESMO issues statement: “shares disappointment”

@myESMO today sent me a Tweet with a link to a statement on their website that says “ESMO shares the disappointment” for the fact that patient advocates, nurses, journalists and other non-prescribers are banned from parts of the forthcoming 2014 Congress in Madrid.

@3NT We support joining w/ other stakeholders to advocate for modif. of EU regs, but duty to respect law http://t.co/7goB3RIXqu #ESMO14

— ESMO – Eur. Oncology (@myESMO) September 15, 2014

While I appreciate ESMO taking the time to make a statement about an issue that has quite rightly attracted a lot of attention, unfortunately it does not address any of the issues raised in this post, specifically there is:

While I appreciate ESMO taking the time to make a statement about an issue that has quite rightly attracted a lot of attention, unfortunately it does not address any of the issues raised in this post, specifically there is:

1) No analysis of the legal regulations in Spain and why ESMO have interpreted them the way they have.

2) No explanation of why the European Society of Cardiology can hold a meeting in Barcelona with no ban on journalists (&others) going into the exhibit hall and satellite symposia, but ESMO can’t.

I would have expected the leadership of ESMO to have talked to the European Society of Cardiology to at least understand how they either got around the rules/regulations or interpreted them differently.

It still makes no sense to me that we can have two large medical meetings, governed by the same EU rules and regulations in the same country within a month, but with two dramatically different responses. ESMO insists it has to follow Spanish rules/regulations, so did the European Society of Cardiology break them and get away with it or did they find a creative solution as suggested in this post?

I would have expected ESMO to be able to offer some explanation on why they adopted a different approach from Europe’s largest medical meeting.

3) ESMO address none of the points raised in this post as to why over the past year since this issue came to the fore at ECCO 2013 in Amsterdam, they did not seek to mitigate some of the effects of the EU directive e.g. by requiring exhibitors to have a booth-within-a booth. Unlike ECCO in Amsterdam, they can’t make the excuse that they didn’t have the time to implement this.

Update Oct 1, 2014: Final Thoughts from ESMO 2014

It’s time to draw this story to a close and this will be my last update on the topic. So what happened at ESMO 2014 in Madrid? Well, in the opening press briefing (which I wasn’t at) several members of the media did ask questions about ESMO’s exclusionary policy towards the press. Apparently this didn’t go down well, which only ended up generating more negative publicity for ESMO:

ICYMI: re ban of pts/advocates, media, & nurses fr #ESMO14 Exhibits & certain activities http://t.co/tEFNM5mLtX — Oncology Times (@OncologyTimes) September 27, 2014

Ed Susman writing in Oncology Times, reported that:

“ESMO President Rolf Stahel, MD, attempted to explain the reason for the ban at a contentious news briefing – claiming that the decision is based on ESMO’s lawyers’ reading of Spanish law regarding advertising to consumers. However, at the larger European Society of Cardiology Congress (August 30-September 3) held in Barcelona (still part of Spain at last report despite Catalonian independence proponents) there were no limits on who was allowed to visit the exhibits.

‘I cannot explain why it was possible in Barcelona and not here,’ Stahel said in response to questions from reporters.”

This begs the question: why Professor Stahel didn’t pick up the phone and ask the CEO of the European Society of Cardiology how they got round the same rules/regs? ESMO have been well aware of the issues raised by this post for several weeks, and have had the comparison to what happened in Barcelona pointed out repeatedly on social media, yet nobody at ESMO had the intellectual curiosity to understand why the ESC Cardiology Congress in Barcelona meeting was different?

Like getting a second opinion from a doctor on a challenging case, it’s hard to explain why ESMO seemed unable or unwilling to seek advice from other medical societies who had faced and dealt with similar issues in Spain.

Instead throughout the Congress and on social media, ESMO has repeatedly sought to justify their actions by blaming Spanish rules and regulations, ignoring the fact that they made their own policy in how they chose to interpret and implement them.

A good case in point being the arbitrary choice of who was excluded based on the type of badge they had for the meeting rather than on whether they were a prescriber or non-prescriber. As far as I am aware, no ESMO member had any restriction placed on them, even if they were a scientist and non-prescriber.

This was reinforced at the registration desk, where media were given badges with a black “PRESS” ribbon attached to identify them to staff (so they would know who to exclude). The person in front of me in the press registration queue was from the European School of Oncology (ESO). Interestingly, his media registration didn’t come with a black Press ribbon. When he queried this, he was told by the hostess handling the registrations words to the effect, “that’s good – it means you can get into the exhibits and all the sessions.” He was told he’d still be able to get into the press room and briefings.

While I am pleased that a media representative from ESO, a partner of ESMO, was not excluded from anything, the double standards at play did leave me with a bad taste. In particular, it was unfair of ESMO to selectively exclude some, but not all, non-prescribers. As a result, they fundamentally failed to address Spanish rules and regulations.

Patient advocates, led by Jan Geissler, also generated a social media campaign (#AdvocatesIn) during the Congress. Several people changed their Twitter avatars (myself included) to show their support!

Despite ESMO protestations that the ban only applied to industry satellite symposia, at the start of the Congress, one patient advocate complained they couldn’t get into one of the educational or scientific session they were actually allowed into, another reported having to assert themselves with staff to get into scientific sessions.

@myESMO Would you please inform your staff that patient advocates can go to sessions? It feels awful to get refused #patientincluded #ESMO14

— Dees (@caseofdees) September 27, 2014

ESMO, to their credit, did correct this error and subsequently apologized. However, this should never happened, and was a further example of the organizational ineptitude on display in Madrid. Indeed, the layout of the ESMO Congress in Madrid (one of my least favorite conference venues) actually made it very hard to restrict access to the exhibit hall as to go from one group of meeting halls to the next or even to the posters, the only practical route was through the exhibit hall.

This was no doubt done on purpose in order to generate maximum opportunity for attendees to be seduced into the exhibit area and interact with Pharma sponsors.

While in theory you could have gone back out to the main entrance and walked around the buildings, this option was impractical in the short time between sessions and there were multiple complaints from those who weren’t allowed to take the main route through exhibit area. No one wants to be made to feel like a second class citizen.

Again, a lack of foresight on ESMO as to how they would implement a ban that restricted access to the exhibits. The net result was by Sunday, ESMO had given up on enforcing the ban as it related to exhibit hall access, as Andrew McConaghie from Pharmaphorum noted on Twitter.

Policy of patient advocates + journos barred from pharma interaction not being enforced. Sensible. #ESMO14 #ESMOlive pic.twitter.com/AsyyDSloz0 — Andrew McConaghie (@pharma_phorum) September 28, 2014

So where do we go from here? Well, ESMO and the patient advocates met on the Monday of the Congress in Madrid and agreed a joint initiative to try and change EU policy as @jangeissler noted on Twitter.

ESMO and patient orgs agree on joint policy action to ensure patient access for future conf #ESMO14#advocatesIN pic.twitter.com/jpoVkWsU7v — Jan Geissler (@jangeissler) September 29, 2014

It is a shame that it took concerted social media pressure for such a meeting to take place. There is no reason why ESMO, in advance of the Congress, could not have consulted key stakeholders from recognized, accredited Oncology Media, European Patient Advocacy groups and the European Oncology Nursing Society about the rules and regulations in Spain and how it proposed to address them at the Congress.

Personally, I think European Patient Advocacy groups and ESMO have little chance of being able to drive changes in EU law. The EU directive on medical advertising has been around for many years, and many other medical societies seem able to work within its constraints without disrupting all stakeholders.

To me, this means the problem has not gone away, and future oncology congresses in Europe will need to consider some of the solutions proposed earlier in this post, such as having a “booth within a booth” and making satellite symposia educational in content, as they are in the United States.

Pharmaceutical companies are well able to handle these solutions and European oncology associations such as ESMO should not be afraid to require the Pharma industry to make the changes necessary so that oncology congresses are as inclusive in Europe, as they are in the United States.

I am glad that this post has lead to a debate; it’s certainly generated a lot of social media impressions and reminded organizations such as ESMO that stakeholders in the oncology community such as scientists, nurses, patient advocates or media take exception to being excluded.

I do hope that next year’s European Cancer Congress in Vienna, organized by ECCO (European CanCer Organization) will not repeat the mistakes made by ESMO, and that it will live up to it’s theme of reinforcing multidisciplinarity.

2 Responses to “ESMO 2014 Cancer Congress bans Press, Nurses and Patient Advocates from Exhibits and Symposia #ESMO14”

Were the posters in the exhibit hall?

According to the ESMO 2014 website, even if you are not allowed to access to the exhibit area, you will be able to view the posters. At ECCO in Amsterdam this did require a long hike as you had to take a detour around the exhibit area.

Comments are closed.