Court rules Medivation has no IP rights to Aragon Pharmaceuticals ARN-509 $MDVN

Medivation investors hoping for a windfall will be disappointed to hear that on December 20, 2012 a California judge ruled the company had no rights to what is now known as Aragon Pharmaceuticals’ ARN-509, a next-generation androgen receptor (AR) antagonist for advanced prostate cancer, similar in chemical structure to enzalutamide (Xtandi).

Enzalutamide (formerly MDV3100) was developed in the UCLA laboratory of Drs. Charles Sawyers and Michael Jung and licensed by Medivation from the University of California. Medivation believed their licensing and sponsored research agreements gave them rights to any follow-on compounds. However, instead of giving Medivation first right of refusal, the University licensed what is now ARN-509 to Aragon Pharmaceuticals, a privately-held company whose owners include Sawyers and Jung.

You can read more about ARN-509 on Pharma Strategy Blog: “Is ARN-509 potentially better than MDV-3100?” Sally Church (@MaverickNY) also interviewed Dr Charles Sawyers in May 2011 just before Medivation commenced a lawsuit against the University of California, Sawyers and Jung claiming breach of contractual agreements.

Concern about the ownership of intellectual property rights to ARN-509 has overshadowed Aragon with many thinking Medivation had a strong case. This has likely hindered the ability to raise capital or obtain a potential partner, although Aragon did announce on October 4, 2012 they had raised $50M in series D financing. However, ARN-509 has been slow to move through development and has yet to enter phase 3 clinical trials.

Based on the limited public information available about the lawsuit between Medivation, University of California and Aragon, my thoughts last year were that the case would settle as none of the parties would want a trial that exposed sensitive intellectual property and financial information.

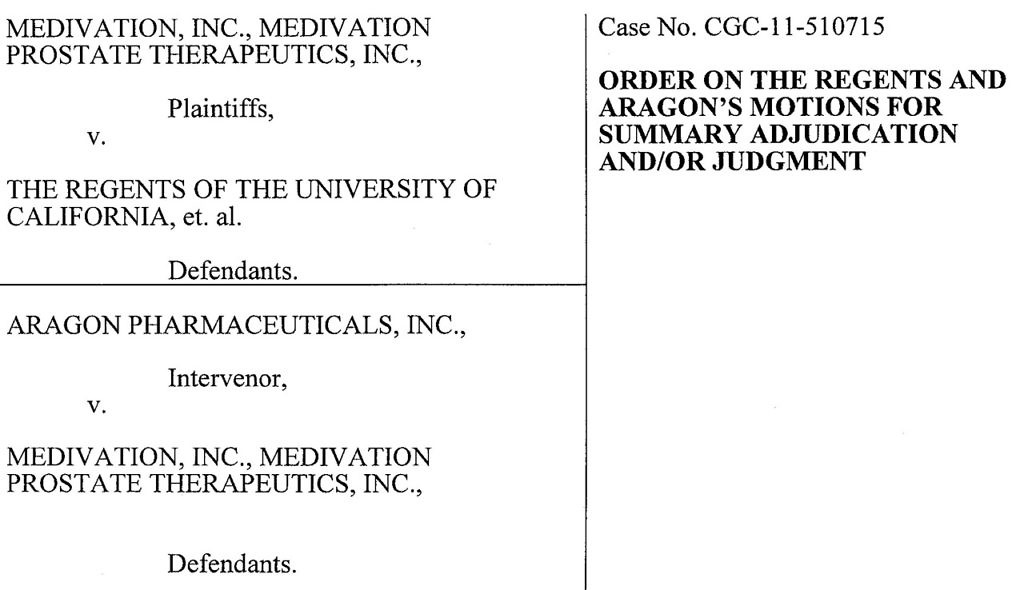

However, in a December 20, 2012 Order, Judge John E. Munter of the Superior Court of California granted summary judgment to The Regents of the University of California on a number of issues, finding that Medivation’s contracts with the University gave them no ownership or licensing rights to ARN-509.

Many thanks to biotech investor (@lomu_j) for sharing the news on Twitter – definitely worth following if you do not do so already.

Superior Court of california ruled friday $MDVN doesn’t have rights to ARN-509. 509 discovered b4 xtandi

— j l (@lomu_j) December 24, 2012

Based on the evidence submitted by the parties, Judge Munter decided that the University of California did not breach the Sponsored Research Agreement (SRA) with Medivation.

According to the court Order, the SRA provided that Medivation would have “a time-limited first right to negotiate an option or license, which may be exclusive” with respect to “Subject Inventions” that occurred during a specified performance period i.e. the University of California was required to disclose follow-on compounds such as ARN-509 to Medivation during this time.

However, anyone who has been involved in contractual disputes will know the devil is in the detail, and the court Order explains why Medivation did not prevail, as many had expected.

The SRA defined “Subject Invention” to be an invention that was “first conceived” and “actually reduced to practice” during the performance period which it was agreed would start on November 1, 2005. However, during discovery The Regents of the University of California presented evidence from a research scientist, Dr Samedy Ouk that A52, the compound that became ARN-509, was conceived and reduced to practice prior to this date. You can read more in the following excerpt from Judge Munter’s Order:

Since the University was only obligated to disclose inventions after November 1, 2005, the court found they did not breach the SRA by failing to give Medivation the right to option or license a compound that was invented prior to this. A close call when you look at the dates, but that is what the parties agreed to in writing.

The court Order discusses several of the claims and disputes between the parties, some of which remain ongoing. It is of course possible that Medivation might appeal, but I was persuaded by Judge Munter’s cogent opinion. In essence the court ruling, unless it is overturned on appeal, means Aragon can move forward unhindered with the development of ARN-509.

Here’s my take from this case:

-

When negotiating a contract, the devil is in the details. Good contract drafting should avoid the need for future litigation. Negotiating contracts can take months, but it’s never wise to sign anything just for the sake of expediency.

-

A contractual dispute can occur years after an agreement was signed highlighting the importance of document retention, e.g. laboratory notebooks, especially where intellectual property is involved.

-

Contracts typically have an integration clause that says what is written reflects the “entire understanding of the parties.” This means a court will only look to what is in written down and not what may have been said or verbally agreed prior to signing the agreement. It’s important to make sure the written contract is clear and unambiguous.

-

IP litigation can delay a potential competitor and deter others from investing or partnering. By the time ARN-509 makes it to market, the prostate cancer landscape will be more competitive than it is today. Through the delay Medivation ends up winning irrespective.

-

Aragon may now be an attractive partner for companies with an established urology/prostate franchise who would like to compete against Medivation.

While many are excited about ARN-509 in advanced prostate cancer, it must be noted that Aragon have yet to show that ARN-509 is more effective than enzalutamide in patients. A phase 3 clinical trial of ARN-509 in the post-docetaxel prostate cancer setting will not be easy given it will most likely require comparison to the current standard of care (Xtandi or Zytiga) and not placebo.

The prostate cancer market remains a dynamic one with multiple new products in development and the potential for combination approaches. The forthcoming ASCO GU meeting in Orlando, from February 14-18, 2013 is worth watching for new updates.

Update May 29, 2013: Medivation announces they will appeal decision in favor of Aragon

$MDVN Filed Notice of Appeal v Aragon – 8K sec.gov/Archives/edgar…

— Colfax (@ColfaxCapital) April 22, 2013

According to the SEC filing that @ColfaxCapital kindly shared the link to last month on twitter, Medivation have not unsurprisingly announced they will appeal the California court decision in favor of Aragon.

The Medivation SEC 8-K filing notes that the appeal was filed on April 15, 2013 and will most likely take 12-18 months, so a California Court of Appeals decision is not expected until sometime in 2014.

There is also ongoing litigation between the University of California and Medivation over whether the company has to make royalty payments to the University when it receives commercial milestone payments from Astellas and a trial on this issue is scheduled for July 2013. Another trial over Medivation’s allegations of fraud against Dr Jung is set to start in October 2013.

There’s still plenty of legs left in this story and a time to go before we have a definitive outcome given that any trial decisions will most likely also be appealed in due course.

Update June 17, 2013: Johnson & Johnson announces acquisition of Aragon Pharmaceuticals with $650M upfront payment

J&J have this morning announced the acquisition of Aragon, and the rights to ARN-509 in a deal with a $650M upfront payment and contingent milestone payments of upto $350M.

$MDVN competitor –> RT @zbiotech: $JNJ purchase of Aragon for $650m upfront plus $350m contingent, close Q3’13

— Adam Feuerstein (@adamfeuerstein) June 17, 2013

Here’s a link to the press release published on the WSJ.

Part of the PPACA signed into law by President Obama on March 23, 2010 was the Biologics Price Competition & Innovation Act (BPCI).

Part of the PPACA signed into law by President Obama on March 23, 2010 was the Biologics Price Competition & Innovation Act (BPCI).

Justice Scalia and Chief Justice Roberts started the oral argument by Vermont’s Assistant Attorney General with concerns that what Vermont was seeking to do was prevent the use of the data by pharmaceutical companies for marketing purposes when it could be used for other purposes such as clinical trials or university research.

Justice Scalia and Chief Justice Roberts started the oral argument by Vermont’s Assistant Attorney General with concerns that what Vermont was seeking to do was prevent the use of the data by pharmaceutical companies for marketing purposes when it could be used for other purposes such as clinical trials or university research. As Justice Sotomayor states in her opinion, “the materiality of adverse event reports cannot be reduced to a bright-line rule.” Matrixx Initiatives, Inc. v. Siracusano, 563 U.S. ___ (2011) (slip op., at 1-2).

As Justice Sotomayor states in her opinion, “the materiality of adverse event reports cannot be reduced to a bright-line rule.” Matrixx Initiatives, Inc. v. Siracusano, 563 U.S. ___ (2011) (slip op., at 1-2).