Inspired by watching the finish of the Tour de France (TdF) today, BSB has been thinking about French railways signs…

William Fotheringham, writing in The Guardian about the TdF, used the warning sign seen on French level crossings of “un train peut en cacher un autre” to describe how Tadej Pogacar followed in the slip stream of Primoz Roglic to unexpectedly win the race on the last stage before Paris!

The idea behind the warning “un train peut en cacher un autre” is the notion that appearances may be deceiving and another train may be coming, in other words you need to be careful and remain observant!

The idea behind the warning “un train peut en cacher un autre” is the notion that appearances may be deceiving and another train may be coming, in other words you need to be careful and remain observant!

It’s a concept that can also be applied to cancer drug development, especially at congresses such as ESMO20 where you have to watch out for the unexpected in the data presented.

The unexpected success of a drug may result in others rapidly following the lead or worse still if there are unexpected side effects, an otherwise promising compound may be condemned to commercial obscurity.

In this two-part post we’re looking at data presented on Sunday at #ESMO20, starting off on with part 1 with a focus on some of the data in early breast cancer and NSCLC.

Was the data as expected or do we need to remain cautious?

To learn more from our oncology analysis and obtain insights and commentary around data being presented at ESMO20, subscribers can log-in or you can click to gain access to BSB Premium Content.

This content is restricted to subscribers

“All that is simple is wrong

But all that is not is useless.”

Paul Valéry, French poet and philosopher (1871-1945). HT Jérôme Galon.

Introduction

I watched an #ESMO20 presentation today for a trial where an unselected group of patients at multiple centers were given a cancer immunotherapy not known to be particularly effective in the disease indication in the hope that someone with a rare histology might respond. Shocking, but true.

What struck me was there was no rationale behind the trial as to why any of the rare sub groups included might potentially respond in the first place. It truly was a case – as far as I could see it – of we’re short of treatment options, everyone wants cancer immunotherapy, so what do we have to lose and maybe we’ll find an unexpected signal somewhere.

While you may obtain an unexpected result, and to be fair there were a few PRs among the majority of non-responders, there was no real curiosity or understanding as to why anyone responded, which made the value of the trial limited in its ability to be applied to others.

The trial was asking a what question? What responses are seen if you give X to everyone.

As we heard from Prof Gerard Evan FRS (Cambridge), major advances in science (and by extension cancer drug development) take place by asking a why question? Why did one person respond and another didn’t?

If you missed it, do read what was one of the most thought provoking interviews we’ve posted on BSB (See posts: Why does Myc drive out T cells? and Gerard Evan discusses inflammation and immune suppression in cancer) because many of his provocative points are rather relevant to ESMO presentations this year.

On Episode 26 of the Novel Targets podcast we also heard Sir Richard Roberts FRS (1993 Nobel Laureate) tell us about many scientists who have won a Nobel prize came across unexpected findings, asked why and probed further to determine the answer.

So what was unexpected at ESMO20 on Sunday?

Let’s look at four oral presentations, two in NSCLC and two in early breast cancer:

1257O – Durability of clinical benefit and biomarkers in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with AMG 510 (sotorasib)

Presented by: David S. Hong (Houston).

Presented by: David S. Hong (Houston).

Presentations slides are available on the Amgen website (link) and QR code. This link was working at time of writing.

I was impressed by this data as I listened to it, and we heard at the end of the presentation it’s been published in the NEJM simultaneously, so do check the paper out if you’re following this area (link):

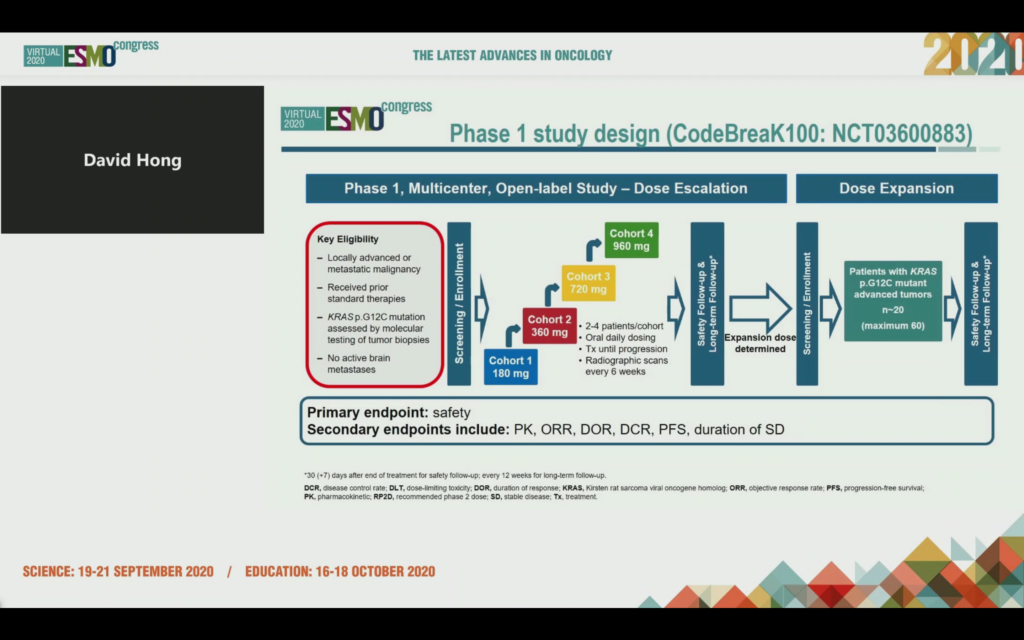

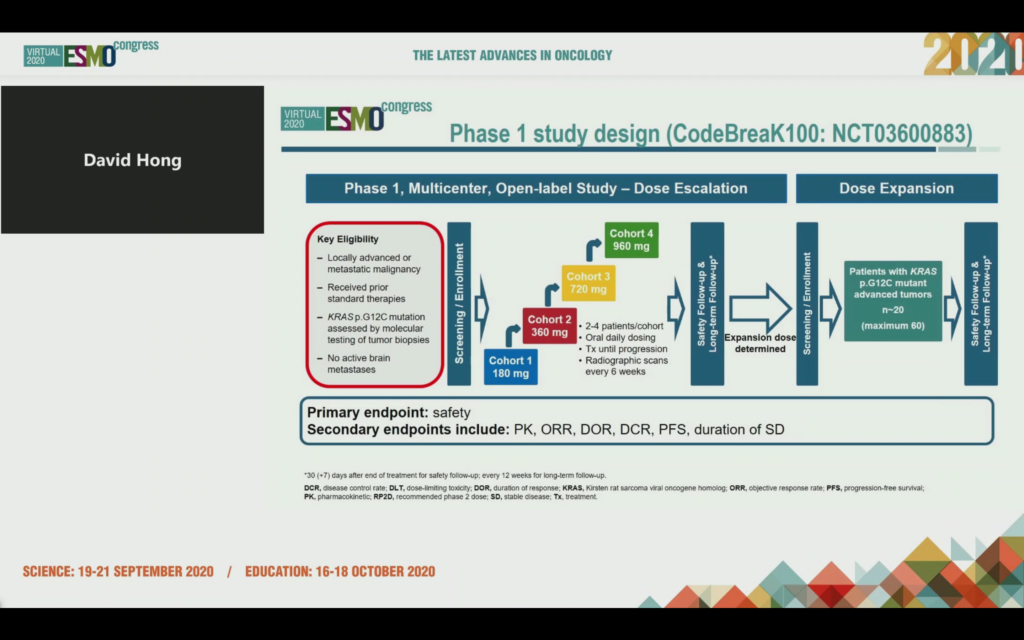

As a reminder, KRAS G12C mutations are found in around 13% of NSCLC, 3-5% of CRC and 1-3% of other solid tumors. In this phase 1 trial cutely named CodeBreaK100, 129 patients across 13 different tumors were given the Amgen KRAS G12C inhibitor, now known as sotorasib (formerly AMG 510). Here’s the study design:

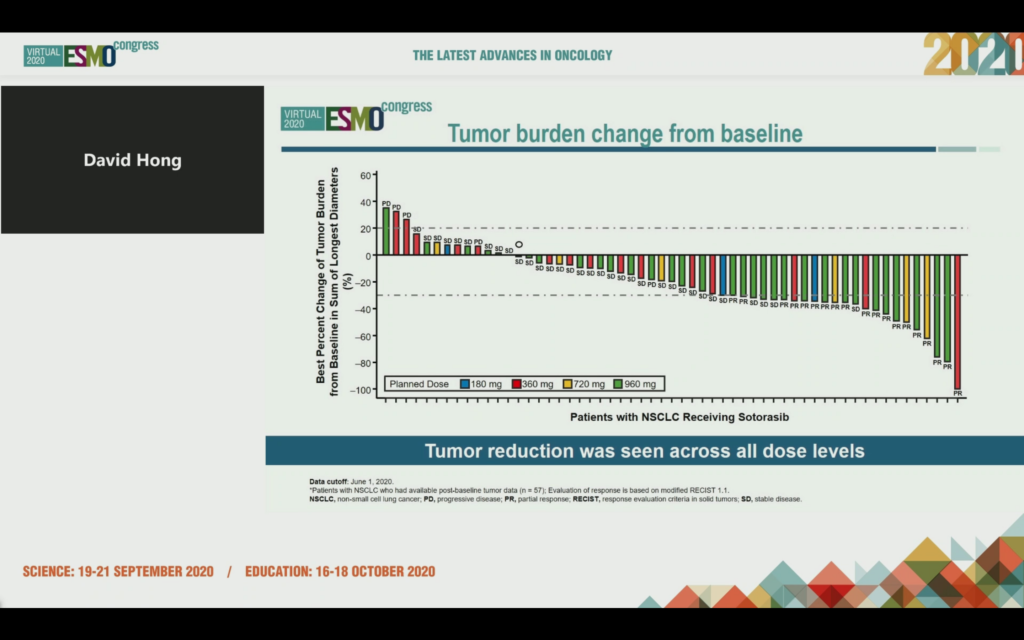

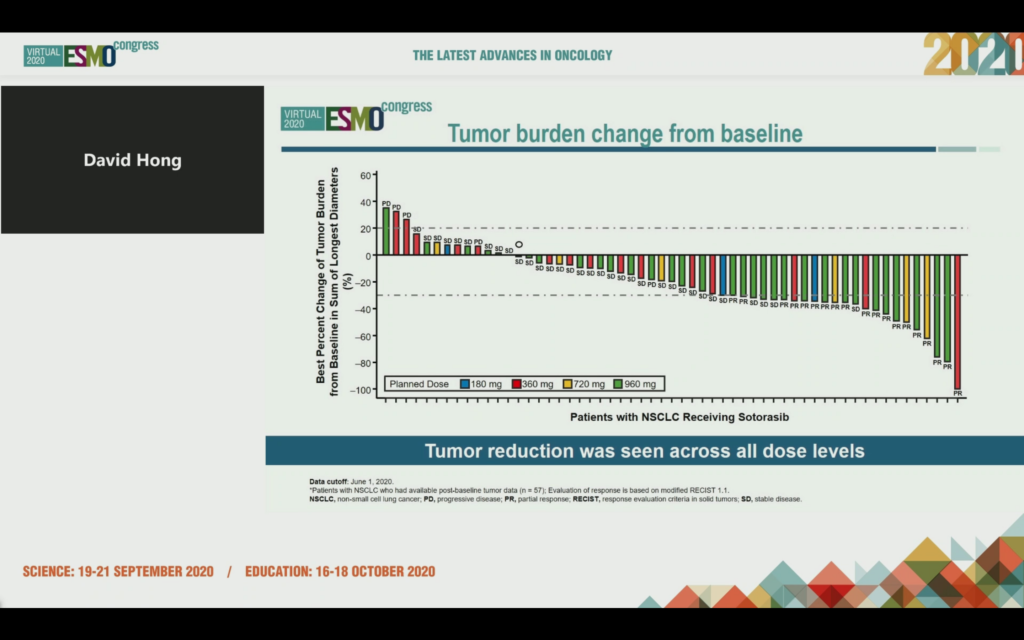

The NSCLC data at ESMO20 showed tumor shrinkage in 42/59 patients at week 6, 19 had a confirmed PR and the ORR was 35%. 10/19 patients were still in response as of data cut off and 960 mg was identified as the RP2D.

Median time to response was 1.4 months, median duration of response (DOR) was 10.9 months and median duration of stable disease was 4 months, with a median PFS of 6.3 months.

Let that data sink in for a moment – with targeted agents (and increasingly immunotherapies) we will often see much shorter PFS and DOR in refractory, heavily pre-treated patients never mind these KRAS mutations portended poor prognosis and were considered ‘druggable’ until very recently.

Interestingly, there was no association between the tissue allele frequency of KRAS G12C, TMB and PD-L1 expression with response! PD-L1 was low in this group of patients and no association with response was seen, nor with TMB.

Also of note was that when co-mutations were looked at, there was no clear mutational profile associated with response:

Responses were seen even if you had co-mutations such as KEAP1, although the ESMO20 discussant, Dr Colin Lindsay (Manchester) did note surprise that LKB1/STK11 was not measured as well given the poor prognosis associated with this mutation, however, he didn’t expect this subset was going to be refractory to G12C inhibitors. Overall, there was no indication of resistance via co-mutations based on the data presented.

As a reminder, we talked about alternative ways to target KRAS, LKB1/STK11, and KEAP1 in our immuno-metabolism series (link).

Dr Lindsay described the development of G12C inhibitors as a triumph of drug discovery and thought the efficacy was impressive for smoking-related lung cancer. It shows proof of principle for sotorasib in targeting G12C mutated KRAS, particularly in NSCLC, but won’t work beyond the G12C mutation.

There remain some of the unanswered questions he raised for consideration:

- How durable are the responses?

- What are the mechanisms of resistance?

- Is there CNS efficacy?

- What are the optimal combo partners?

- Can you combine G12C inhibitors with immune checkpoint inhibition?

- Do we need a phase 3 trial?

Dr Lindsay noted in terms of RAS precision medicine, G12C is the tip of the iceberg with increasing promise of upstream and downstream inhibitors. We’ve written about the potential for targeting SHP2 and SOS1, for example, and these are likely combination partners. Of relevance to this issue, Mirati Therapeutics now have collaborations with Novartis (SHP2) and Boehringer (SOS1) to pursue combination trials with their KRAS G12C agent, MRTX849. I don’t think this is a reflection of lack of activity per se, but savvy and experienced new product folks quickly recognizing combinations are the logical way forward if they want to induce more lasting effects that tackle known resistance mechanisms.

Amgen have additional CodeBreaK trials ongoing evaluating sotorasib as monotherapy, and also in combination with a variety of other anti-cancer agents (CodeBreak 200, CodeBreaK 200, CodeBreak 101 and CodeBreak 105) and once we see more data I expect there’ll be more clarity on their development pathway. In case you missed, it there was a trial in progress poster describing CodeBreaK 200 at ESMO20 (poster 1416TiP):

“A phase III multicenter study of sotorasib (AMG 510), a KRAS(G12C) inhibitor, versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring KRAS p.G12C mutation.”

Take home: The early data is impressive, perhaps more than expected, but there’s still a lot of work to do to understand how durable the responses are, the underlying mechanisms of resistance, and optimal combination strategies going forward.

1258O – Amivantamab (JNJ-61186372), an EGFR-MET bispecific antibody, in combination with lazertinib, a 3rd-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), in advanced EGFR NSCLC

Presented by: Byoung Chul Cho (Seoul, Korea).

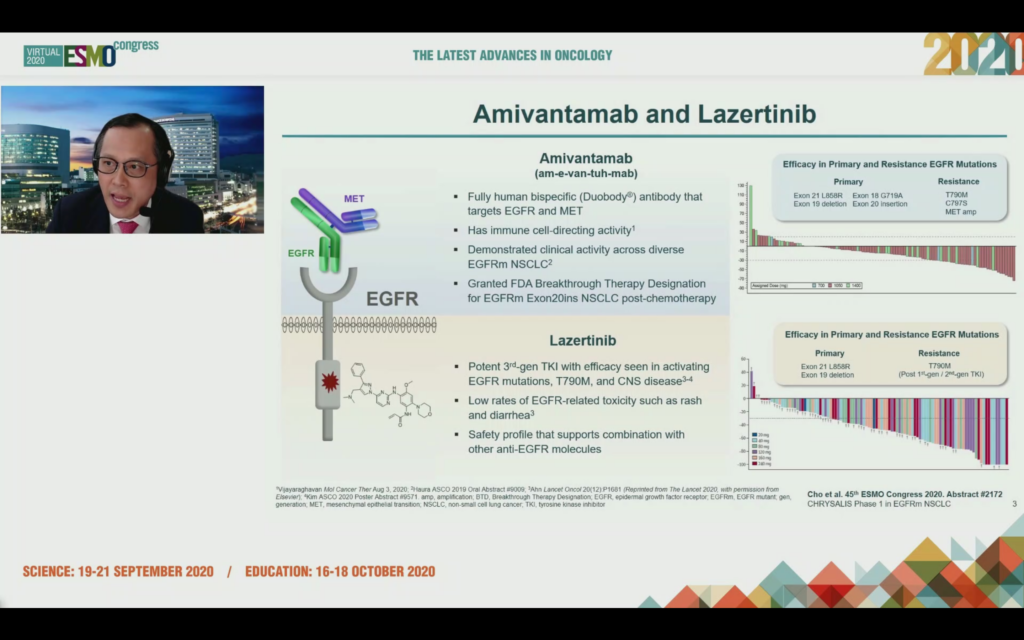

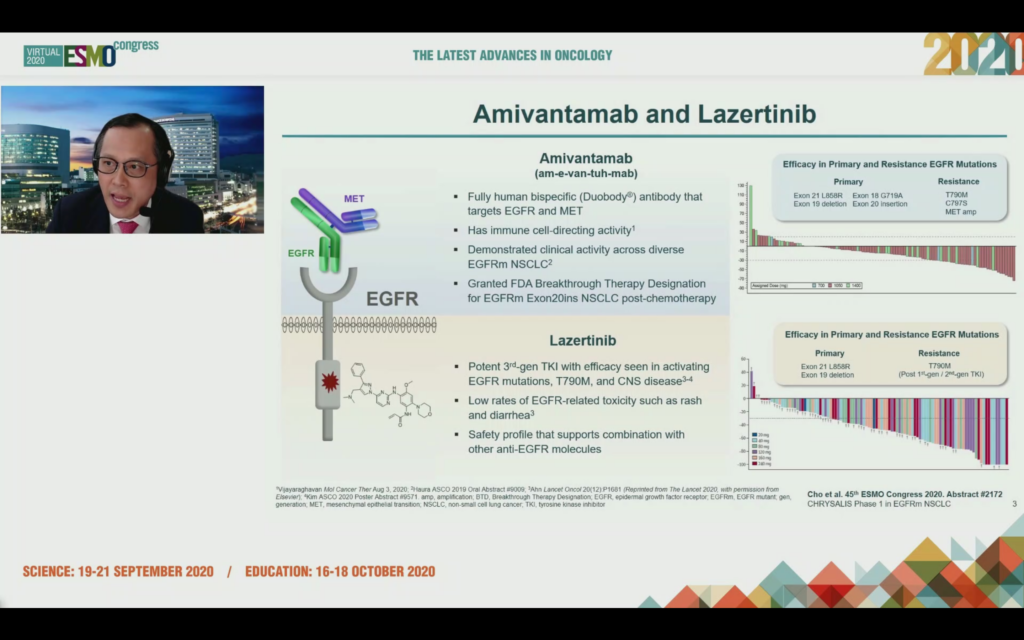

There’s a lot of interest in the combination of amivantamab, a bispecific antibody from JNJ that uses Genmab’s duobody platform to target EGFR and MET, which is being combined with lazertinib, a 3rd generation TKI licensed from Yuhan in Korea.

Earlier this year (see Mar 10, Press Release), Janssen were granted FDA Breakthrough Therapy Designation for amivantamab for the treatment of patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) Exon 20 insertion mutations, whose disease has progressed on, or after platinum-based chemotherapy.

The third generation TKI lazertinib shows efficacy in primary and resistance EGFR mutations and the theory is that combination of these two agents may delay emergence of resistance without increasing toxicity.

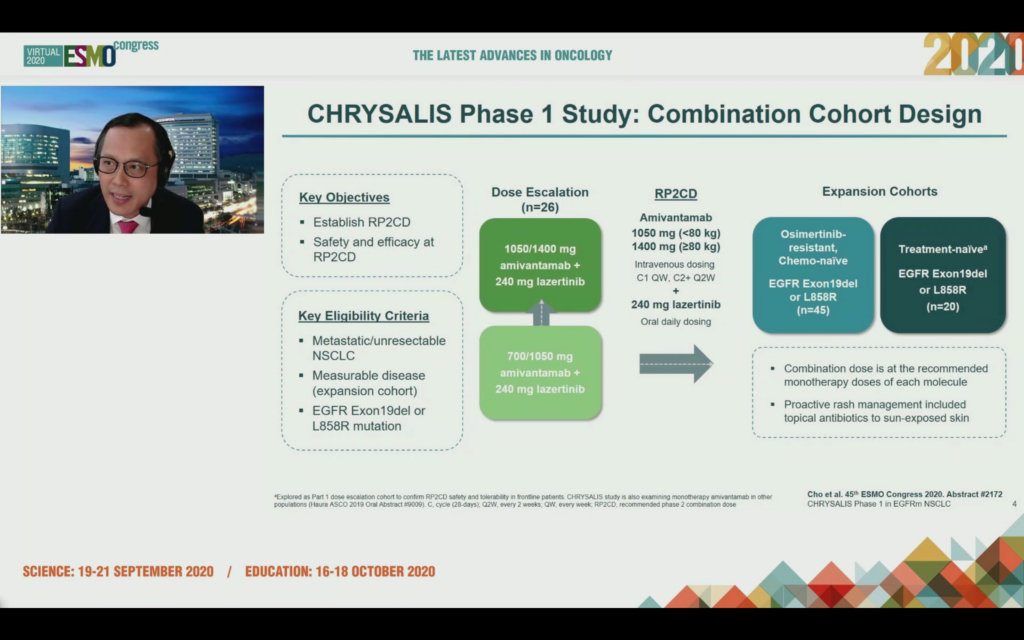

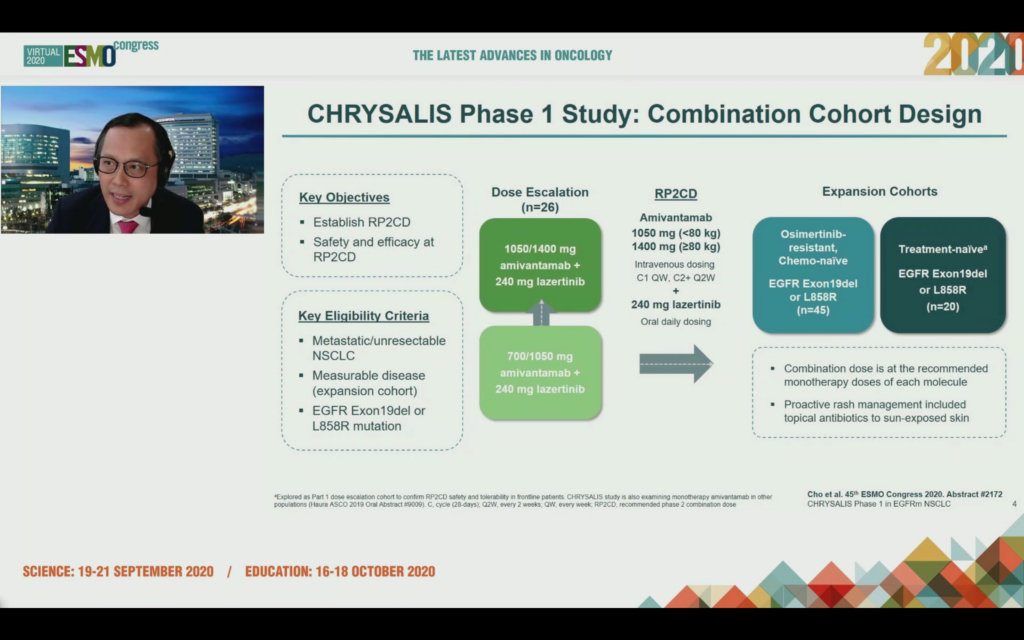

At ESMO20 the results of CHRYSALIS phase 1 study were reported by Dr Cho, here’s the study design which was intended to establish the RP2D, with expansion cohorts in osimertinib resistant, chemo naive, and treatment naive EGFR patients with an Exon19 deletion or L858R mutation.

What did the results show?

In the osimertinib-resistant cohort of patients there was an ORR of 36% observed with 1 CR and 15 PR out of 45 enrolled with a median follow up of 4 months.

Describing the 36% response rate in the osimertinib-resistant patients as “respectable” (a much better description than modest in Brit-speak), the discussant Dr Colin Lindsay (Manchester) noted the median follow up is only 4 months. We definitely need to see more data on how durable all the responses are with longer follow-up.

There were 20 patients in the chemo-naive cohort, all of whom responded, with 20 PRs for 100% activity and a median follow up of 7 months.

For sure, 100% sounds impressive – and I’ve seen that number bandied about by the media – but I’d caution this is a small exploratory sample size with immature data and the confidence interval range is 83-100.

For reference, consider the 556 patient phase 3 FLAURA trial in the front-line setting where osimertinib had an 80% response rate compared to 76% in the standard EGFR-TKI group (See: Soria et al in NEJM 2018 (link).

One of the major benefits we’ve seen with osimertinib since its development is that it has a much lower level of rash than many other EGFR inhibitors. We’ve seen this from the get go – it’s a major advantage when it comes to patient quality of life, as we heard from Dr Pasi Jänne back in 2015! Here are a few of the posts we’ve written while following this story in case you want to revisit them:

2015: AZD9291 EGFR T790M NSCLC data at European Lung shows longer PFS (link)

2016: Osimertinib front-line data wows European Lung 2016 (link)

2019: Insights on osimertinib in 1L NSCLC from the lens of the FLAURA trial (link)

Let’s consider another reference point when you look at the FLAURA trial data for first-line EGFR NSCLC, which was published in 2018 in NEJM (link). There was a 58% incidence of rash (any grade) with osimertinib compared to 78% (any grade) for the control arm of standard EGFR-TKI.

While I don’t want to make a cross trial comparison – we’re dealing with different patient populations and trial sizes after all – but for context, the percentage of rash seen in CHRYSALIS-1 (any grade) was 85%.

This is not far off the dermatologic incidences for the highly unpopular EGFR inhibitor afatinib, which has a number of dermatalogic side effects such as acneiform eruption (≤90%), erythema of skin (≤90%), skin rash (≤90%), paronychia (11% to 58%), xeroderma (31%), pruritus (10% to 21%), cheilitis (12%)… and has never taken off commercially as a result.

To me, this suggests lazertinib may end with an incidence of rash closer to standard EGFR TKI’s. If this is the case and the data are reproducible then osimertinib would have an advantage in this important quality of life related adverse event. Is this a deal breaker? Definitely not in an osimertinib-resistant population where there is a need for new treatment options. In considering the market opportunity, we’d also have to consider 4th generation EGFR inhibitors in development, which may be effective in this indication too and compare how they stack up.

It also raises the key question of whether J&J could potentially have licensed a better EGFR TKI than lazertinib?

Dr Cho mentioned that the Phase 2 CHRYSALIS-2 trial had started in osimertinib-resistant and the chemotherapy-relapsed settings. This could be a potential path-to-market strategy and the FDA BTD will no doubt help facilitate this, assuming the data are up to snuff.

Another thing we will need to know more about, in order to be able assess the potential of this combination, is what are the resistance mechanisms?

Naturally, we see resistance with all TKI’s – it’s a function of the selective evolutionary pressure – we’re not curing patients just turning EGFR mutant lung cancer from a acute into a chronic disease. Dr Cho did mention the CHRYSALIS-1 data was being analysed in terms of resistance mechanisms, so we should look forward to this data in due course.

Dr Lindsay, in his ESMO20 discussion, did note the proof of principle for targeting EGFR and MET was shown earlier this by Dr Lecia Sequist and colleagues, who published data in Lancet Oncology on the TATTON trial, however, he didn’t want to compare the trials. [Reference: “Osimertinib plus savolitinib in patients with EGFR mutation-positive, MET-amplified, non-small-cell lung cancer after progression on EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors: interim results from a multicentre, open-label, phase 1b study” (link).]

As an aside, it’s worth noting there were two deaths on TATTON (cause unknown), which is a red flag for the osimertinib plus savolitinib combination.

In addition to looking at efficacy in osimertinib-resistant patients, JNJ are to be congratulated for wanting to take on osimertinib in a head-to-head phase 3 trial in the first line setting to investigate whether the combination of amivantamab and lazertinib is superior and delays time to resistance by targeting both EGFR and MET.

Dr Colin Lindsay did pointedly note, “FLAURA has set a high bar to crack with osimertinib monotherapy.” Having followed the development of osimertinib (and rociletinib) for several years, I share those sentiments. There’s an old saying, if you go after the king you better not miss, and I do worry about having a combination therapy which includes an IV formulation is far from ideal.

To me, the efficacy in the first-line setting would need be to be far superior to overcome this, especially if your AEs and QoL profile is not as compelling. The CHRYSALIS-1 data presented at ESMO20 shows encouraging activity, which is worthy of further investigation and only by doing the head-to head trial will we truly know how it compares to osi.

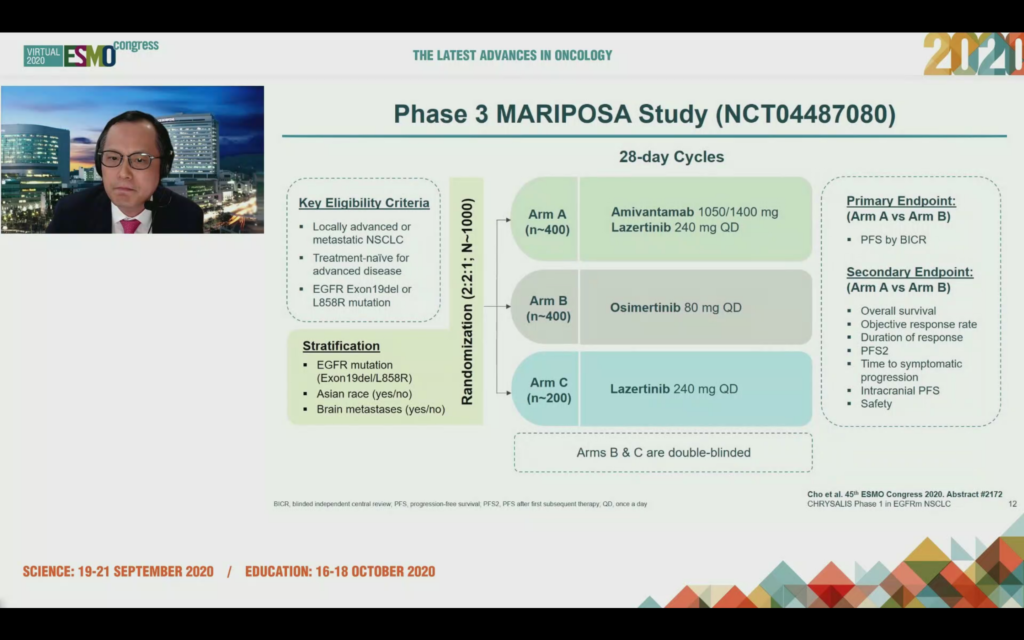

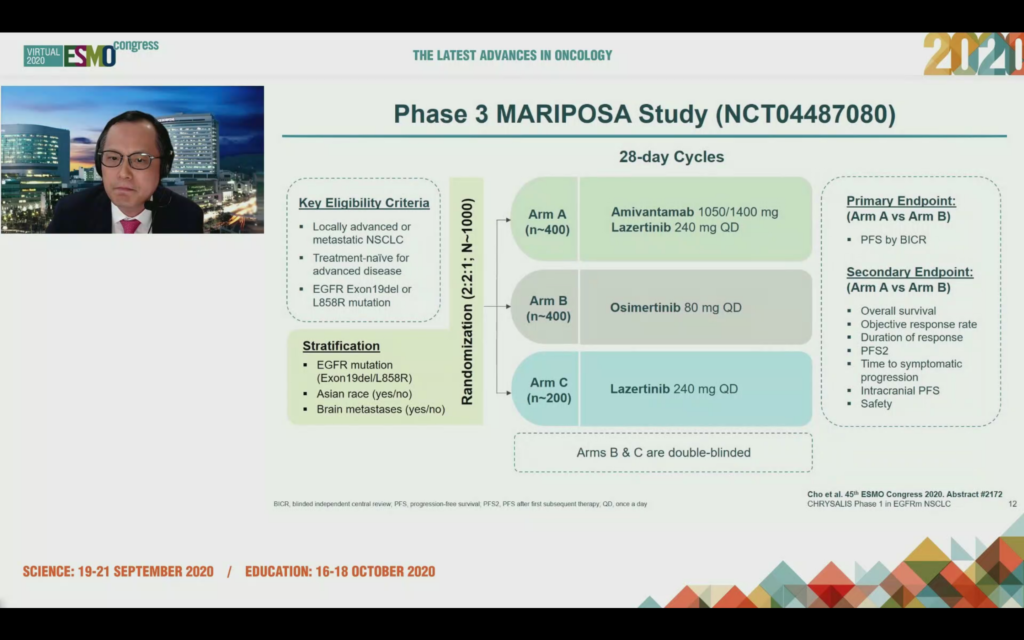

Dr Cho mentioned the MARIPOSA trial has just started in frontline EGFRm NSCLC vs. osimertinib. It’s not shown as recruiting yet on clincialtrials.gov (NCT04487080) and it will be interesting to see in the time of COVID-19, how long it takes to accrue a 1000 cancer patient trial:

In the Q&A, Dr Cho stated osimertinib has a shorter PFS in the Asian population (at least those he treats – he may have a higher number of adenocarcinoma patients who are smokers or ex-smokers), thus there is an unmet medical need in the front line setting and if the amivantamab and lazertinib combination has a significant increase in PFS in this population it would be the preferred line of treatment.

Ultimately, the success of this combination will come down to whether the MARIPOSA data is compelling or not.

Dr Lindsay also pointed out if IV drugs are potentially returning to EGFRm front line treatment then there may be issues arising around quality of life, patient access, and also resource limitations in hospitals, especially in Covid-19 times.

Would you rather take a pill or have to take a pill and go to a clinic or doctor’s office for an IV infusion as well?

Take Home: Sorry to disappoint all those BSB subs really excited by this data and I know a few of you are, but I’m going to go against all the hype by saying the ESMO20 data has not convinced me that amivantamab and lazertinib will be the winner in the front line EGFRm setting. That said kudos to JNJ for going for it and the MARIPOSA trial will answer the question.

However, I do see the potential of new therapies to address an unmet medical need in osimertinib resistant patients, but would argue this is a much smaller commercial opportunity. CHRYSALIS-2 and MARIPOSA are definitely trials to watch.

LBA11 – IMpassion031: Results from a phase III study of neoadjuvant (neoadj) atezolizumab + chemotherapy in early triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)

Presented by: Nadia Harbeck (Munich, Germany)

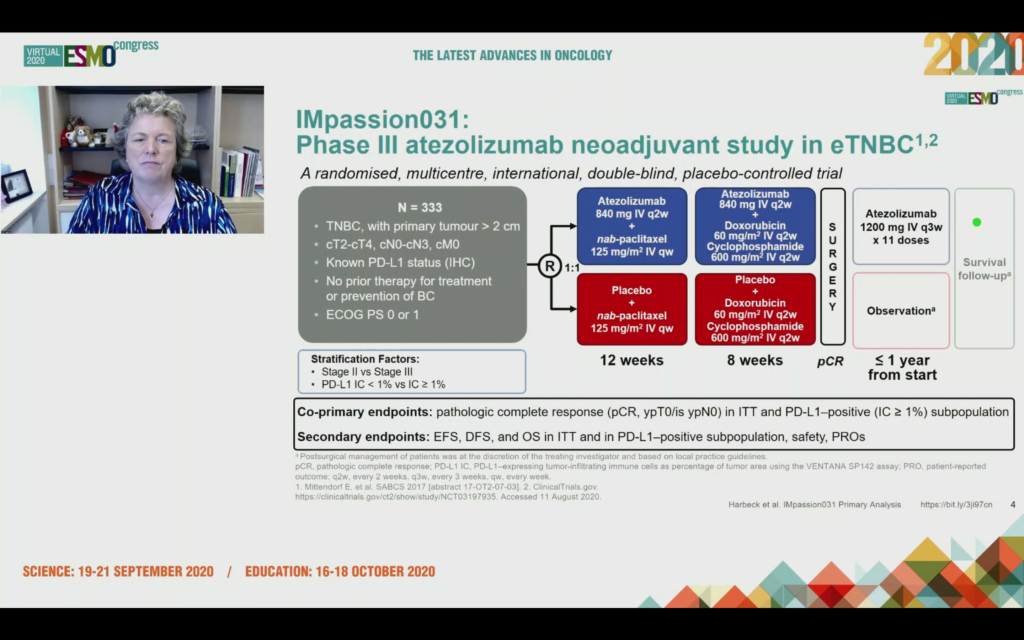

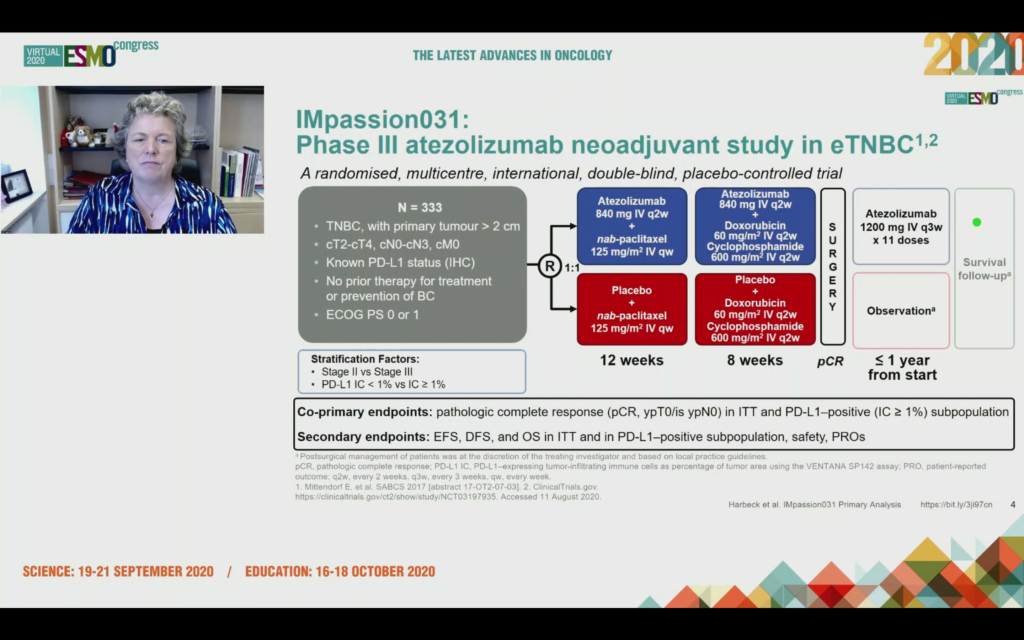

The data presented at ESMO20 for the IMpassion031 trial of atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel chemotherapy in early triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) was simultaneously published in The Lancet (link). I’ve not had time to read the paper, so the comments below are based on Prof Harbeck’s ESMO presentation (link to slides) – at time of writing they are not yet available, but hopefully they will eventually post.

Here’s the trial design:

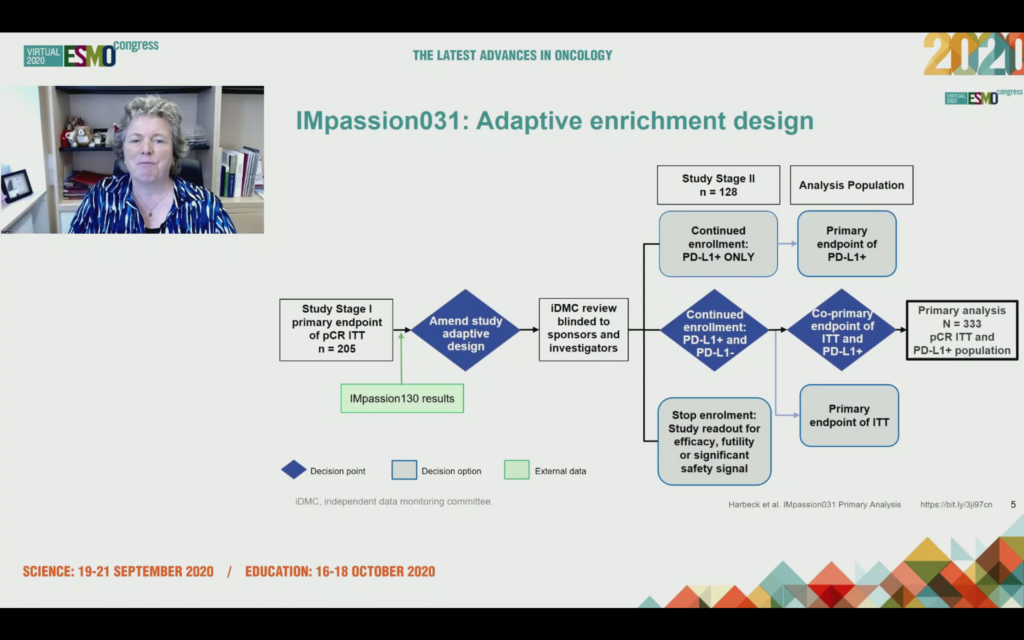

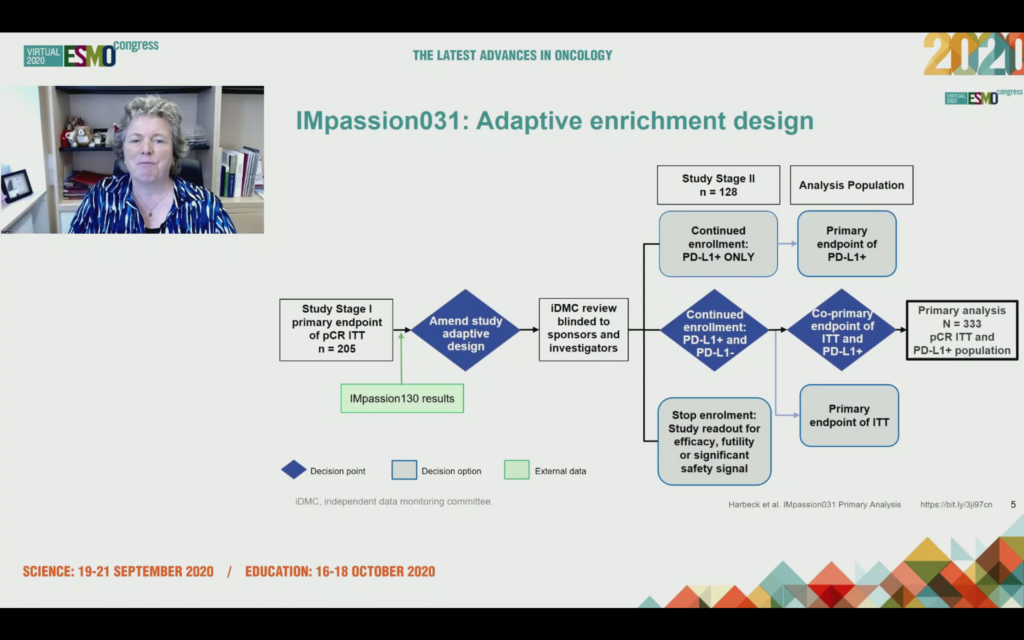

What was unexpected to me was to hear after enrolling 205 patients, the data monitoring committee were asked to consider should the trial continue enrollment with PD-L1+ patients only, in other words we only expect to see benefit in this group, or should it proceed with the ITT analysis that included PD-L1+ and PD-L1-?

The answer was the trial should continue on an ITT basis i.e. allcomers with a co-primary endpoint of ITT and PD-L1+.

Given we’ve already seen positive data for pembro plus chemo in neoadjuvant TNBC (KEYNOTE-522 presented at ESMO19 by Peter Schmid in the Presidential Session), a positive result might well be expected.

What was unexpected to me, however, was there was only a statistically significant difference in pCR rates between chemo arm and chemo plus atezo arm in the ITT group, and not in the PD-L1+ group!

In the ITT population (i.e. allcomers) those patients who were PD-L1+ and PD-L1- receiving atezo plus nab-paclitaxel had a pCR rate of 57% (95/165) compared to 41.1% for nab-paclitaxel plus placebo (69/168). This 16.5% difference was significant (p=0.0044).

In the co-primary endpoint of PD-L1+ tumors, however, the pCR rate of 68.8% (53/77) for atezo/chemo versus 49.3% for placebo/chemo didn’t cross the significance boundary accounting for the adaptive enrichment design. Prof Harbeck repeatedly used the word “advantage” to describe the higher pCR rates seen in the PD-L1+ atezo+chemo arm, even if technically the co-primary endpoint was not met! It’s like “trending to OS”, either you met your endpoint or you didn’t.

From a commercial perspective, being able to give the drug irrespective of PD-L1 status opens the door to use in more patients and the company produced slides describing the findings as, “benefit was observed irrespective of PD-L1 status and that this new combination therapy may offer an improved curative option for this patient population with high unmet medical need.”

Several questions jump to mind:

- Why wouldn’t you expect a PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor to work better in those who have high PD-L1?

- Why do PD-L1 negative patients respond?

- Were the trials balanced for stromal TILs? (see: NeoTRIPaPDL1 trial presented at ESMO20 we previously discussed)

- Did stromal TILs correlate with pCR?

- Who needs PD-L1/PD-1 checkpoint immunotherapy to reach a pCR, who can make it with just chemo and are there patients with high stromal TILs who don’t need any additional therapy at all ?

We discussed many of these issues in our coverage of ESMO19 last year.

The ESMO20 discussant, Prof Sherko Kuemmel (Essen-Mitte), compared the data (cross trial comparison warning!) to KEYNOTE-522, raising the question of which chemotherapy backbone should you use with a checkpoint and whether the benefit of carboplatin on pCR would translate to overall survival?

Prof Kuemmel also made the point that “PD-L1 status is a different biomarker in early TNBC vs mTNBC” and I think there’s a lot within this comment to consider.

Could the reason why atezo only seems to work well when combined with nab-paclitaxel in TNBC and pembro appears to work well with several chemo combinations be down to the PD-L1 assay and the populations defined? Although there is some overlap, we know the assays don’t identify the same patients, in other words someone who is PD-L1+ with one assay may not be PD-L1+ be the other assay!

We’ve seen PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoints fail in indications where others work and I remain unconvinced the drugs are fundamentally different, and that they are not a similar class of compounds. The difference may be in what we are measuring with the assay or in nuanced subtleties of trial designs.

It was disappointing not to see some stromal TIL data for the IMpassion030 trial and one has to hope it will be presented in due course later because I think we need to understand why some people respond in TNBC and others don’t, and this data may offer insights. Just giving everyone a PD-L1 checkpoint plus chemo isn’t the answer.

Take Home: In order to work out who will benefit from immunotherapy, we may need to think differently about how we define immune system activation in early stage TNBC, especially given PD-L1 may not cut it as a reliable biomarker. Stromal TILs could be one way to look at this, which takes us on to the next presentation where sTILS were evaluated.

159O – Prognostic value of tumour infiltrating lymphocytes in young triple negative breast cancer patients who did not receive adjuvant systemic treatment; by the PARADIGM study group

Presented by: Vincent M. de Jong (Amsterdam).

ESMO have put out a write up about the key points of this presentation so do check that out for the key points (link), but to set the scene for what was unexpected we need to go off on a tangent…

BSB asked Prof Adrian Hayday FRS at AACR19 what he thought of the seminal work of Jérôme Galon, and he replied Dr Galon would make his top 10 of cancer immunologists! We don’t disagree.

Dr Galon was before his time in realizing that tumor staging did not predict outcomes in stage 2/3 colon cancer, but you could predict outcome based on the immune response to the cancer. He went on to develop an algorithm called Immunoscore, which was spun out by INSERM to Marseille based HalioDx who have since commercialized this assay. They’re now developing an artificial intelligence based version.

Here are links to some of the prior posts around Immunoscore if you are new to BSB or missed them:

2015: Immunosurveillance, Immunoscore & Personalized Cancer Immunotherapy – interview with Jérôme Galon (link)

2016: How do you calculate Immunoscore? A tour of HalioDx (link)

2016: HalioDX CEO Vincent Fert outlines commercial strategy for Immunoscore in US and Europe (link)

2017: How to revolutionize cancer immunotherapy trials – interview with interview with Jérôme Galon (link)

Immunoscore, as developed by Dr Galon has only been validated for colon cancer (see: Lancet 2018 paper, “International validation of the consensus Immunoscore for the classification of colon cancer: a prognostic and accuracy study“) but there is no reason why the concept cannot be applied to other early cancer types.

I was struck listening to Dr de Jong’s talk at ESMO20 that we may be at the early stages of a revolution in how we could think about early TNBC… and I have no doubt many in the breast cancer community are already thinking along these lines.

HalioDx are looking at Immunoscore in other tumor types including Breast Cancer. There’s a poster at this meeting exploring this: 1984P: “Tumour infiltrating lymphocytes in early breast cancer: High levels of CD3, CD8 cells and Immunoscore® are associated with pathological CR and time to progression in patients undergoing neo-adjuvant chemotherapy.”

If stromal TILs are a biomarker which are predictive of pCR and long-term survival and they can be measured by standardized techniques, including artificial intelligence then could we potentially develop a novel way of staging early TNBC patients, in the same way Immunoscore turned the traditional tumor staging of colon cancer on its head?

Dr de Jong presented data at ESMO20 for a population based study in the Netherlands, which investigated all their patients under 40 years of age diagnosed between 1989-2000 who were systemic therapy naive, N0, were classified as triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), and for whom stromal TILs were scored according to guidelines.

Out of 3,517 patients identified in the Netherlands Cancer Registry, 2717 pathology materials were retrieved, out of which 485 were classified as TNBC resulting in 481 samples evaluable for stromal TILs. For more on the measurement of stromal TILs see Kos et al, 2020: “Pitfalls in assessing stromal tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (sTILs) in breast cancer” (open access link) and the International Working Group website.

The stromal TILs were correlated with outcome, namely overall survival (primary endpoint) and distant metastasis free survival (DMFS).

What de Jong and colleagues found is sTILs are prognostic for OS with an excellent survival for patients with high sTILs. If you had sTILs > 75% and that was 22% of the patients (n=107) then 93% of that group were still alive at 15 years!

There are of course nuances to this data, but what struck me listening to Dr de Jong was that the survival data based on stromal TILS did not correlate with the tumor staging and tumor size, which reminded me of Dr Galon’s work. Classical tumor staging does not reflect the immune response and immune profile and that is ultimately what matters as to whether you live or die.

If your immune system is turned on and targeting the cancer them you will live longer than if it’s not – it really is that simple going back to the Paul Valéry quote at the beginning of this post, but underlying this nuanced concept is a lot of complexity.

So could you develop an AI based system to measure stromal TILs and use it as a novel way to stratify patients and which therapies they should receive in early TNBC? If you can do it for colon cancer then why not in breast cancer?!

Take Home: We may end up having to re-think how we think about classifying cancers and if we do, then we may be better able to deliver precision immunotherapy to those who need it.

In the style of the film Jerry Maguire where Jerry sets out his manifesto for the “Future of Our Business,” we’re taking an extended look at the Future of Natural Killer (NK) cell therapy through the eyes of one of the leading global translational scientists in the NK field, Dr Todd Fehniger, who is at Washington University in St Louis.

In the style of the film Jerry Maguire where Jerry sets out his manifesto for the “Future of Our Business,” we’re taking an extended look at the Future of Natural Killer (NK) cell therapy through the eyes of one of the leading global translational scientists in the NK field, Dr Todd Fehniger, who is at Washington University in St Louis.

The idea behind the warning

The idea behind the warning  Presented by: David S. Hong (Houston).

Presented by: David S. Hong (Houston).

A conference can be like watching the Tour de France (TdF) which ends this weekend. If you’re standing on the route, you wait a long time for it to come along and then the peloton passes by in a flash. We experienced this in London back in 2014, where there was only a brief moment of time to capture the memory.

A conference can be like watching the Tour de France (TdF) which ends this weekend. If you’re standing on the route, you wait a long time for it to come along and then the peloton passes by in a flash. We experienced this in London back in 2014, where there was only a brief moment of time to capture the memory.